73:e Venice Film Festival: Report 2

By Moira Sullivan

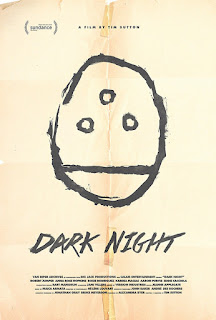

Tim Sutton’s Dark Knight was featured as a special screening at the Venice Film Festival 31 Aug - 10 September. The film is is part Frederick Wiseman and part Gus Van Sant. These are two filmmakers whose talent has been a problem for some spectators and who are praised by others. Both have crews which set up shots perfectly and both have acquired funding for professionally made films. The content is revealed often in long takes with little dialogue, quickly edited scenes (editor Jean Applegate) and redundant imagery. Introspection with lingering momentum is their watchdog. Their films are part reality TV, part commercial voyeurism and almost always a male gaze. Focus is on male characters and when, for example, it is on female characters such as Wiseman’s long surveillance of a battered women and children he did not seem to know much about women. (Interview with Wiseman for Filmfestivals.com at Venice 2001), so much that he went on to make Domestic Violence 2 the following year, where a woman is arrested for attacking her husband.

In Dark Knight written and directed by Sutton, the surveillance cameras are pointed at young people in a low income area where mall shopping and painting fingernails help pass the time. (Six youth are chronicled played by Anna Rose Hopkins, Robert Jumper, Karina Macias, Conor A. Murphy, Aaron Purvis and Rosie Rodriguez). The young people either skateboard, swim, go to the movies, dye their hair orange, use Google maps (as does cinematographer Hélène Louvart, The Wonders, 2014), Skype, ride around in cars, and fill their universe with “nothing”. To make this film, Sutton uses guns, darts, butt shots and masks. Male characters (and one woman) act out their rage and women shop, pose for selfies in their underwear or lie in bed listening to men.

Two women play the guitar and sing “You are my sunshine…But if you leave me and love another, you'll regret it all some day” with a gun pointed at their heads unbeknownst to them. That this triste existence is pervasive is evidenced by repetitive aerial shots of the neighborhoods where restless youth live. They don’t read books, converse with one another, attend school or change the world in any way. Conversation between counselors, young men, young women and support groups are on the fringe of the empty pictures that pose as landscape, but not in any Antonioni sense. These are the real discussions beneath the constant numbing of youth, the realities they don’t want to know about, to hear about or see. Freeways, tract homes, parking lots, green grass, and recurrent mall lights resurface as the momentum builds for a brutal gun attack. We know that it is coming like the slithering slide of a snake as it approaches its prey and is ready to pounce. The vacant dead eyes of the perpetrator should give pause to the victims or anyone he sees. But they walk innocently in scenes that put the spectator in a voyeuristic trance, we who are the voyeurs, waiting for the pounce and the carnage. Listening to a young man claim that humans are not real but animals, and for his mother to claim he is smarter than his peers is one of the many internal contradictions in the film, as if brutal acts are committed by geniuses. We know that he is going to kill his turtle when he holds it up on several occasions. In that regard he demonstrates that animals aren’t real either. We know that the sunshine singers are going to be blown away and all the scantily clad young women who check their phones and take selfies. Video games don’t lead to violence, says the young man who later takes a hammer to the turtle. Humanity raised on artificial tech culture, without support, in low income neighborhoods and nuclear families, confined to gender roles, produce numb brains that have no connection to people. The contorted faces of men and women who scream reveal the angst that so many keep inside. In that respect the scenes that build up to these contortions, are the real violence.

Dark Knight's carnage, is a real life occurrence at a movie theater, that claimed the lives of young people, many with bottled up rage, just like their shooter. “You make me happy… the skies are grey… please don’t take my sunshine away are the slow languid lyrics (arrangement by Maica Armata) heard before the shooter enters the theater by a back door designed for mall security. We don’t see turtles killed or humans. We are suspended as victims while the snake slithers.

The year is 2012, Aurora Colorado.

© 2016 - Moira Sullivan - Air Date: 09/14/16

Movie Magazine International

Movie Magazine International

Comments

Post a Comment